-Mark Twain

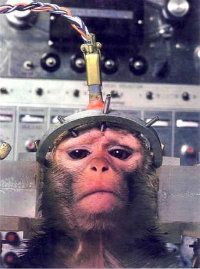

One important aspect of veganism which is often overlooked by the mainstream media is the lifestyle's stance in avoiding products and ingredients tested or experimented on animals. Animal testing, which includes toxicology tests and biomedical research for pharmaceuticals, is commonly used in applied commercial industry research as well as pure research in many Universities and Medical schools.

In

2009 the United States reports over 87,000 dogs and cats used for these

types of research and experimentation, as well as over 70,000 nonhuman

primates.[1] Estimates for the number of rats and mice used in tests and research in the United States alone were found to be 80 million in 2011.[2] An article by the British Medical Association's Journal of Medical Ethics points out that animals used in these forms of research do feel pain, and are incapable of understanding why they are being hurt.[3] Worst yet, many of the forms of research are not at all necessary for scientific or medical advancement, such as toxicology tests for cosmetics and house-hold cleaning products. These products are readily available from companies which do not perform such tests.[4]

While many argue against the use of animals for these

means, surveys have found that many approve of it's use as necessary for

medical advancement.[5] While this is usually an insistent ideal for

western progress, the reality is results from such research are

questionable and require careful consideration and trial to compare to

that of voluntary human subjects.

Comparing animal studies with human outcomes

Researchers with the Journal of the American Medical Association warned on the reliability of animal research saying "patients and physicians should remain cautious about extrapolating the

finding of prominent animal research to the care of human disease … poor

replication of even high-quality animal studies should be expected by

those who conduct clinical research."[6] Differences in anatomy, metabolism, and physiology for test animals can cause results to vary greatly between human and animal test subject. A common example is in the active ingredient of Tylenol, Acetaminophen, being poisonous to cats but a reliever of pain to humans.[7] Many examples such as this exist, including differing results in the same species of animal. These differences become more apparent in variations of sex, weight range, breed, as well as age.

The last few decades of medical history are rife with stories of cures to human diseases after artificially infecting and, later through research, curing said diseases. "We have cured mice of cancer for decades - and it simply didn't work in humans," said Dr. Richard Klausner, director of the United States National Cancer Institute in 1998.[8] The New England Anti-Vivisection Society reported in 2008 that chimpanzees, used as subjects of AIDS vaccine testing for some twenty-five years, have been abandoned for scientific and cost-benefit reasons as an unwise and unethically unjustifiable source of further research due to "substantial differences between chimpanzee and human responses to HIV infection and the course of the disease".[9] These are not the only instances where little progress has been made at the expense of ethics. In 2004 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Lester Crawford said 92% of all drugs having successfully passed through animal studies fail in human clinical trials.[10]

The most classically recognizable example of a medical discovery being delayed due to the wasted time, money, and efforts due to attempts to create an animal model of a human disease, however, was in the discovery that smoking cigarettes increased one's risks of lung cancer. The finding, reported in 1954, was dismissed because lung cancer could not be induced due to the inhalation of cigarette smoke in animal models.[11] It was not until thirty years later that the United States Surgeon General released it's warning on cigarette packages across the country.

Advancements in alternative research and cruelty-free testing

The only Federal law in the United States which regulates the treatment of animals in testing and research is the Animal Welfare Act (AWA). This law excludes most kinds of rats and mice, as well as all forms of birds, all of which make up 95% of all laboratory subjects. The proposals placed by vegans and anti-vivisectionists (those against the acts of experimenting on, cutting, or dissecting living animals) are to find and use alternatives to the hit or miss practice of animal testing.

The philosophy and ethics to these alternatives are approached very differently. Wherein an animal tester may artificially induce a disease onto a confined animal for observation, clinical investigators observe the same effects on humans which are already ill or have died. The use of high throughput cell cultures in experimentation is also very promising. This practice, also known as in vitro, was used in 2010 for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to test the chemical dispersants used to clean up the oil gushing from the broken wellhead in the Gulf of Mexico.[12] Toxicological exams are also being approached with in silico biology, which is computerized modeling. In silico tools are in many respects the forerunners to the development of furthering many greater tools in toxicology.[13] The Johns Hopkins University Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT) is one of the leading forces in these developments, and releases many up-to-date studies and research pieces relating to the advancement of these alternatives.

The philosophy of veganism to abolish the exploitation of animals becomes an easier reality to imagine with these advancements in alternative testing. Many Universities and research centers have found facilities to these alternatives to be surprisingly cost-effective, and the hope is to do away with older and unreliable animal tested practices. The future seems brighter with possibilities.

Bibliography

1. United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, "Annual Report Animal Usage by Fiscal Year," February 10, 2011

2. Carbone, L. "What Animals Want." Oxford University Press, 2004, 26

3. Thomas, D. "Laboratory animals and the art of empathy." Journal of Medical Ethics, 31, April 2005, 197-202

4. Coalition for Consumer Information on Cosmetics, "Cruelty-free compassionate shopping guide"

5. Aldhous, P, Coghlan, A. "Let the People Speak." New Scientist, May 1999

6. Daniel G. Hackam, M.D., and Donald A. Redelmeier, M.D., "Translation of Research Evidence From Animals to Human," Journal of the American Medical Association 296, October 11, 2006, 1731-2 (Kaste M. Use of animal models has not contributed to development of acute stroke therapies: pro. Stroke. 2005;36:2323-2324)

7. Allen, A. "The diagnosis of acetaminophen toxicosis in a cat", The Canadian Veterinary Journal, June 2003, 44(6): 509-510

8. Simmons, M, et al. "Cancer-Cure Story Raises New Questions." The Seattle Times, May 6, 1998

9. Bailey, J. "An Assessment of the Role of Chimpanzees in AIDS Vaccine Research." Alternatives to Laboratory Animals, June 28, 2008, 36: 421

10. Harding, A. "More Compounds Failing Phase 1." The Scientist, August 6, 2004

11. Doll, R, Hill, A. B. "The Mortality of Doctors in Relation to Their Smoking Habits." British Medical Journal,1(4877): 1451-1455

12. Perkel, J. "Animal-Free Toxicology: Sometimes, in Vitro is Better." Science magazine, March 02, 2012, 1122-1125

13. Hartung, T. "Food for Thought ... on In Silico Methods in Toxicology." Johns Hopkins University Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing, ALTEX, February 2010